We often get asked what our opinions are around LLMs, and investing in companies that use LLMs as differentiation. This is a complicated topic that deserves a thorough answer. To expedite the conversation, this blog post helps to explain the origin of our bearish position on public LLMs as a core technology.

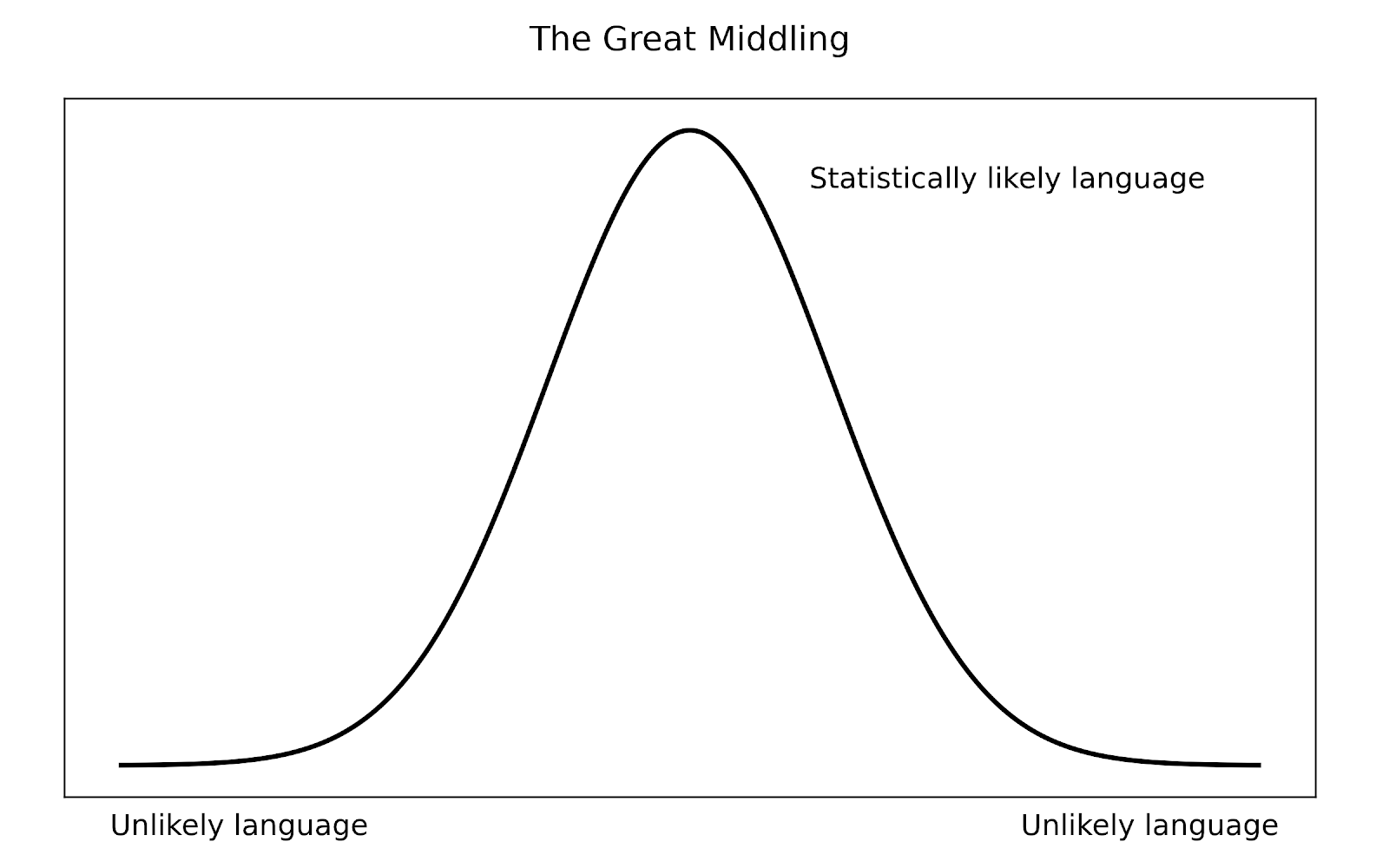

Imagine a bell curve. At its center lies the safe, familiar, and average; the phrases that everyone uses, the ideas that everyone repeats. Out at the edges live the rare, the controversial, the untested, the radical. Human progress, after scaling ideas to institutions, has always depended on those edges. Yet, as language is increasingly filtered through large language models, those tails are the first to disappear. What emerges is what I refer to as the great middling.

The process doesn’t require many assumptions. Large language models are trained on public data. People then use those models and learn from them. They post their outputs back onto the public Internet. In tandem, organizations and individuals attempt to shape what models know and how they respond. Taken together, this creates a feedback loop where language folds in on itself. Each cycle pushes generative models closer to the mean.

The Why

This happens because LLMs are not databases. They do not store knowledge in a way that preserves the richness of each expression. Instead, they compress human language into a high-dimensional vector space, where probabilities govern how words cluster together. In that statistical compression, what is common rises to the surface, while what is rare becomes downweighted.

Some ideas are simply snipped out because they are disfavored by the engineers building the models. These suppressed or censored ideas disappear altogether. Or perhaps they are rarely articulated on the public Internet while common on the Dark Web which is still accessible but unindexed. Entire categories of thought that have never yet been articulated remain absent from the model’s space. These are areas that are ripe for research but have not yet been discovered or explicitly enumerated. The result is a conceptual bell curve of language where the middle swells with probability mass and the tails thin out to the point of obscurity or invisibility.

Language that falls out of the model’s training set, or gets strangled by the mean, tends to do so in one of three ways. Some thought is dissident or rare: outsider philosophies, unconventional science, minority art, non-Western epistemologies, extreme religions, etc. Some thought is censored or deliberately excluded, either because it is taboo, politically inconvenient, or deliberately filtered out by the model’s creators because it is unsavory and makes the model builders look bad. And finally, some thought is simply absent because it has not yet been articulated at all. This last category is perhaps the most suffocating, since it prevents the LLMs expression of anything that does not already exist in human discourse.

Here is one way to visualize it conceptually is with a literal bell curve:

The middle represents the trained consensus, the safe, and dare I say bland, average region that language models reproduce most readily. The edges represent dissident, censored, and missing categories of thought. It is precisely in those regions that new philosophy, politics, psychology, art, and technology emerge. Yet these are the very regions that are thinned out or erased altogether under repeated cycles of statistical training. As more data is produced on the Internet the middle grows, but the edges stay the same, making them even less statistically likely to appear in the output.

This matters because history’s breakthroughs have always lived at the margins. The heliocentric universe. The theory of relativity. The Socratic method. Entirely new forms of government. Radical art movements. Each began as an outlier, a low-probability thought on the linguistic bell curve. When language itself becomes subject to iterative compression, those edges are shaved off. Consensus no longer emerges organically but is reinforced algorithmically. The model is both shaped by and reshapes the world, by starving the conditions in which novelty emerges.

The effect is not neutral.

The middle is an arena of influence, and whoever controls the training corpus and model biases controls the middle. That power is too valuable to ignore. Maligned actors can skew it deliberately, pulling the distribution toward conspiracy or disinformation. Politically motivated groups can nudge it toward their ideology, creating the illusion of consensus where none exists. Corporations with enough reach can bias LLMs toward ad campaigns, branding, and slogans until commerce itself shapes the very structure of thought. The great middling is a long game with winners and losers. One loses by the culling of thought.

Granted new ideas will emerge when coaxed out by the users who inject their own novel ideas one by one. However, even if the ideas are important or useful they will be too rare to survive the compression to the mean. The only path of survival of novel ideas is amplification by the Internet writ large or by the model engineers who tip the scales of the weight against the mean. But we believe this will not happen at the same pace as the middling.

The So What for Investors

For investors, this ecosystem raises an obvious red flag. Companies whose technology core depends on generative LLMs are building on an ever weakening foundation. If companies use LLMs that have trained on the Internet after the year 2020, the LLM is training on incestuous middled data. Their outputs inevitably converge toward the middle, making them indistinguishable from competitors doing the same thing. Worse, their work products are constantly at risk of being folded back into the training pool, further diminishing their distinctiveness. It becomes the business equivalent of a fax of a fax of a fax, where the resolution of each iteration is worse than the last.

By contrast, there are generative use cases we believe have some value. While a model trained on social chatter is doomed to middling, companies that treat LLMs as a supplement to proprietary, specialized data have a path forward. A model trained on unique corpora avoids a collapse into generic outputs because the inputs are unique to the use case, not widely available, and cannot be replicated at scale. In the computer security vertical, examples might be: HTTP logs, passive DNS logs, Netflow, or other narrow domains. That distinction between “core built on the generic” and “supplement applied to the unique” is everything when it comes to defensibility.

Unique training data is the only moat we see in the use of LLMs as applied to cyber security challenges.

The unique data itself may be investable, not the LLM.

Companies that build LLMs are potentially at less risk because their business models are not derivative of LLMs necessarily, but rather in offering subscriptions to those models or advertising models atop the LLMs. However, we are concerned that there are nearly 2 million models on Huggingface at the time of this post, so even that moat appears to be dwindling as more competitors enter the space with multi-modal models, both small and large language models alike.

The great middling, then, is an investment risk. Progress, insight, and competitive advantage all live at the tails. Unless a company has exclusive access to those tails, its product and its future will collapse into the middle along with the rest.